It was a simple question: “What are you reading at the moment?” The reaction was interesting, and spoke volumes.

Several colleagues had talked to me about this person. “You should interview them*. They have decades of experience in their field. They would be a great resource for you.”

We met for a cup of coffee and a chat about the financial world. We were trying to figure out how we can help each other in our respective fields, and I wanted to tap into their expertise.

What I discovered surprised me: Much of this person’s approach is based on assumptions that have been proven to be false by innumerable researchers and academics. Further, they aren’t aware of any of the research.

So I took a different tack. I figured that I’d try to get an idea of their professional reading list to see what they were exploring. Hence my question.

The response came after a momentary stare: “Oh, I don’t have time to read. I’m far too busy with my work and other responsibilities.”

No reading, no research, no awareness of work that gives the lie to many of the myths and practices that are common in this particular field.

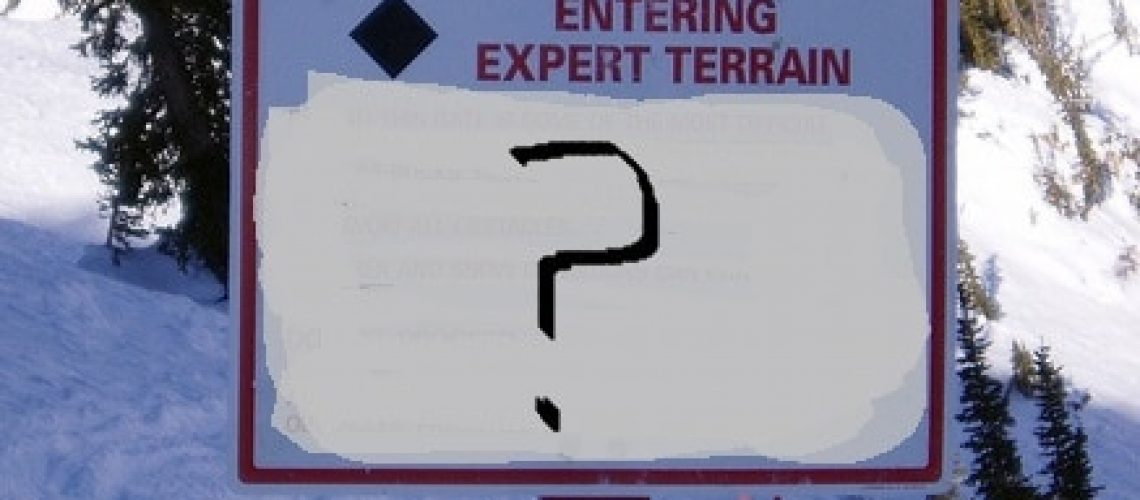

I wrote about the question of who, exactly, is an expert a few years ago in this blog post, and I’ve been digging into it ever since. This latest experience made me wonder: Do time and experience on the job make you an expert?

The answer is pretty clear: no.

K. Anders Ericsson, the Conradi Eminent Scholar of Psychology at Florida State University, has spent his academic career researching the development of expertise. A summary of some of his key findings is available in this article published in Harvard Business Review. Ericsson’s research is also discussed at length in the book Influencer, The Power To Change Anything by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, David Maxfield, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler.

Ericsson’s work reveals that there is no correlation between expertise and time in the field. The authors of Influencer add the following: “A twenty-year veteran is no more likely to be more skilled than a five-year rookie by virtue of time on the job. Any difference has nothing to do with experience and everything to do with deliberate practice…. Most professionals progress until they reach an acceptable level, and then they plateau; they stop learning.” (The emphasis is mine.)

Time is certainly a necessary component, but it’s not the most critical factor for mastery. What matters more is how you use your time. Ericsson suggests that the necessary ingredient for expertise is deliberate practice.

Deliberate practice

The authors of Influencer summarize Ericsson’s concept of deliberate practice as follows:

“It’s the skill of practice that makes perfect. It requires the following:

1. Full attention for brief intervals; steely-eyed concentration.

2. Immediate feedback – constructive and sometimes painful – against a clear standard. Study with well-informed teachers.

Compare yourself to the best and learn quickly from your mistakes.”

People who are genuinely interested in developing expertise spend time working on areas in which they are not strong. People who have stopped learning simply focus on the areas in which they are already comfortable. These are the people who “don’t have time to read.”

Ericsson provides the following example: Olympic skaters spend their time working on difficult elements they have not yet perfected. Club skaters focus on routines with which they are already familiar and comfortable. Amateurs spend a good chunk of their time socializing while on the ice. In all three cases, the skaters spend the same number of hours on the ice with very different results.

It would be great if deliberate practice were fun, but it’s not. In fact, it’s downright frustrating, tedious, and demanding. It’s also necessary if you really want to become an expert.

I have experienced a small measure of this. Perhaps the most salient example was when my parents moved me from a kindly (but ineffective) piano teacher to a not-so-nice and demanding lady who got results. I didn’t like her, nor did I enjoy my time with her, but she made me a much better pianist. I started winning competitions and mastering notoriously difficult pieces. After my Grade 9 Board examination, the examiner asked if I had plans to continue professionally; he would consider providing a recommendation. That wasn’t part of my goals, but I was nonetheless grateful to my piano teacher for the magic she had worked on me.

How did she do it? She made me focus on single bars, one hand at a time, until I mastered every note and every nuance of the bar. She allowed me to move on only when I had reached a level of fluency that satisfied her. She also demanded that I practice every day, and I did.

When I tried to play through errors, she would admonish me. “You’re wasting your time. Don’t bother practicing if that’s how you’re going to do it. Don’t skip over the errors, work on them.” Harsh, but right. And effective. She clearly applied the principles of deliberate practice.

Who, then, are the experts?

The suggestion that expertise plateaus after only a few years on the job without further deliberate practice has far-ranging implications. Just think about all of the people in your life who are presented as experts – medical, financial, educational, and so on. What are they doing to get better? How are they honing their skills?

- Are they continuing to learn from sources that challenge their thinking and their assumptions?

- Do they continue to seek out the latest information, research, or approaches in their field?

- How and from whom are they obtaining educated feedback? Recall that we all need regular, constructive, and occasionally painful feedback against a clear standard.

- Are they measuring their performance against the best in their industry versus the average?

- How much time do they dedicate to deliberate practice, giving their full attention on an ongoing basis to improving the areas in which they are weak(er)?

When you start to apply these criteria, you begin to look very differently at “experts”. We may be a touch generous in our assumptions regarding expertise, which matters if we depend on these people for advice, guidance, or representation. If, for example, they handle your money, you want to know that they are working with research-based information.

The person I met for coffee is engaging, well-intentioned, and experienced, but they are not an expert despite decades in the business. Their approach is also potentially ineffective since it’s based on outdated information.

The good news is that expertise can be developed by anyone. You just need to understand that time, alone, in a pursuit won’t cut it.

*I’ve used gender-neutral pronouns deliberately to preserve anonymity.